I remember two notes about scale from high school art history. The first is with respect to the Venus of Willendorf. The statue, made between 28,000 and 25,000 BCE, is 11.1 centimeters (4.4 in) high. It does not have feet that would make it freestanding. It was found in Lower Austria in 1908 (near Willendorf), but is carved from a red limestone that originates 136 km northeast of there. Without knowing that, though, the size and feetlessness are clues as to the fact that this was an object in the possession of a nomad. It is small enough to be carried; it is small enough to be carried a long distance when the carrier need pack other things as well; and it need be carried, because it cannot stand to be viewed.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Rocks in the Forest of Fontainebleau, 1860/1865, oil on canvas, 46 x 59 cm (18 1/8 x 23 1/4 in.)

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Rocks in the Forest of Fontainebleau, 1860/1865, oil on canvas, 46 x 59 cm (18 1/8 x 23 1/4 in.)

The second note I remember from high school is with respect to the departures many Impressionist painters made from the artists of the official Salon. In place of large-scale work, their paintings were often small. They could work outside because paint became commercially available in the 1830s, and so they could work faster and investigate everyday subject matter in terms of its temporary, temporal conditions, resulting often in perceptible brush strokes. All of this changed the notion of what constitutes a finished work of art. These paintings, unlike the Venus of Willendorf, were meant to be viewed rather than carried for ritual purpose (unless viewing is that), but looking at them one can still see that smallness means something here. The way they were made is a constituent part of the value of the work and it belies the notion of larger size as innately more powerful. The small size also made the paintings easier to buy for the new bourgeoisie of the 19th century.

Andreas Gursky, Rhine II, 1999, Chromogenic color print, 61 ¼ x 10’ 1 ½ inches (155.6 x 308.6 cm)

Andreas Gursky, Rhine II, 1999, Chromogenic color print, 61 ¼ x 10’ 1 ½ inches (155.6 x 308.6 cm)

As an undergraduate majoring in photography, I became frustrated with the notion that size is so underconsidered in photography. People talked about small prints being intimate and large ones being like history painting, commanding attention, but those blanket statements never did it for me. I did have an experience the year I graduated from college, 2000, of seeing Andreas Gursky’s Rhine II at MOMA during his retrospective and realizing that in order to really be with the picture, I had to walk its sidewalk, and that that required steps. I liked that physical response, and the tie it suggested between the print’s size and its subject.

For the most part, however, photographic prints at the end of the 20th century were big, without tremendous consideration to how big, or why, beyond references to painting and cinema. On the other hand, in the middle of the 20th century, photographic prints were generally small, and the choice of dimensions here was mostly a default, rarely considered beyond the capacity of the photographic negative to fill the page without pixelating: 5 x 7 inches, 8 x 10 inches, 11 x 14 inches, 20 x 24 inches. (Forgive me my ignorance of the metric equivalents.) I began to notice after college the fact that many camera-based photographers would make editions of their work in multiple sizes, charging less for the smaller sizes and also less for the first tier of the edition sold, and so on. I couldn’t imagine why they wouldn’t have given any particular thought to which size best suited the work. What would it mean for photography – or for any medium, but camera-based photography especially because its relationship to size is so theoretically manipulable – to resist manipulation?

I have spent the years since the year 2000 thinking about scale a lot, and I have been reminded to do so in St. Petersburg, especially yesterday after a studio visit with artist Petr Shvetsov, who is based here, and an opening at Luda Gallery with the Oslo-based collective, Locus. Questions of significance in art often start with very practical issues, and this, with respect to the issue of scale, is especially true.

Shvetsov’s studio is on the 7th and top floor of an otherwise residential building with no elevator. He has had this studio for years and it is full of the accumulation of experiments and interests as much as it is full of – and as much as they are a part of – artworks.

One is ushered through the studio door through the shadows of birdcages and into a large atelier one can abandon briefly on the building’s ledge through an open window.

One is ushered through the studio door through the shadows of birdcages and into a large atelier one can abandon briefly on the building’s ledge through an open window.

Inside, Shvetsov is working on a variety of projects: some small, some large, but all essentially made where they need to be made and afforded their size accordingly.

One type is a graphite drawing from his imagination: a forest landscape in three vertical panels. The landscape is rendered darkly, with detail in these darks, but two irregular circles of brighter rendering draw attention to certain regions of the picture plane. Like spotlights with no beam or the lens of some kind of scope, they make emphasis of nothing in particular, scanning the junctures of fallen trees for meaning.

One type is a graphite drawing from his imagination: a forest landscape in three vertical panels. The landscape is rendered darkly, with detail in these darks, but two irregular circles of brighter rendering draw attention to certain regions of the picture plane. Like spotlights with no beam or the lens of some kind of scope, they make emphasis of nothing in particular, scanning the junctures of fallen trees for meaning.

On a practical level, the scale and material of this drawing is such that it wouldn’t have been done in situ in the landscape; the marks would take too long to execute outside – the paper would be wet with dew by then – and there would be nothing flat enough big enough outside to pin it to to make the marks anyway. These aspects of its form are legible; without even talking to the artist, then, one might know that he made it in the studio, if not from his imagination. On another practical level, getting it out of the studio and down the seven flights of stairs is a matter of rolling each panel up.

In another corner of the studio, Shvetsov is growing bacteria from tea into jelly-like planes that drape and oxidize on top of slim bent steel (hangers?) Here, the material itself determines its scale, although he may ostensibly limit it. These and other such experiments become small, mutable sculptures that again are portable. They require supports, as do the drawings – and as, for that matter, did the Venus of Willendorf – but unlike the Venus of Willendorf, the supports are built into the sculptures he puts together, which might, I suppose, be understood as scientific assemblage.

In another corner of the studio, Shvetsov is growing bacteria from tea into jelly-like planes that drape and oxidize on top of slim bent steel (hangers?) Here, the material itself determines its scale, although he may ostensibly limit it. These and other such experiments become small, mutable sculptures that again are portable. They require supports, as do the drawings – and as, for that matter, did the Venus of Willendorf – but unlike the Venus of Willendorf, the supports are built into the sculptures he puts together, which might, I suppose, be understood as scientific assemblage.

Much of another wall is taken up by a grid of small paintings that Shvetsov does on vacation during the summers. The underpainting of all of these is a hot pink, from which the oil paint on top derives a fantastic glow. They are landscapes, initiated en plein air quickly, often in the fifteen minutes or so before sunset, and clearly the small size helps him carry the stretched canvas, hold it, make the sketch, and take it back to his temporary studio, wherever that may be, to layer in further observations from memory with the occasional improvised encaustic or varnish. The light in these is carefully observed, even in the darkest of paintings, and yet by an inverse logic the practiced speed of their making – and their portability – is a part of the equation that makes that possible.

Much of another wall is taken up by a grid of small paintings that Shvetsov does on vacation during the summers. The underpainting of all of these is a hot pink, from which the oil paint on top derives a fantastic glow. They are landscapes, initiated en plein air quickly, often in the fifteen minutes or so before sunset, and clearly the small size helps him carry the stretched canvas, hold it, make the sketch, and take it back to his temporary studio, wherever that may be, to layer in further observations from memory with the occasional improvised encaustic or varnish. The light in these is carefully observed, even in the darkest of paintings, and yet by an inverse logic the practiced speed of their making – and their portability – is a part of the equation that makes that possible.

Shvetsov also works in installation. These are not in his studio, per se. He shows one on the computer:

Detail, Tanya, 2013, Tiles on wall, 118 x 314 in.

This, he made for a show at American University’s Katzen Art Center in 2014.

It is a wall of tiles that he glued to the Katzen’s wall, and then that he carefully removed to cut with a tile cutter until a pattern suggesting brute force emerged. The work is ostensibly about the fall of the Soviet Union, but in general in this post I am eliding subject matter and focusing on form and its relationship to the artist’s needs and the social and practical space of making and moving art.

Given Shvetsov’s interest in biological patterning in his studio, it is hard not to see in this careful chaos a kind of nature’s math. (I love Wikipedia’s definition of cracking so much that I will link to it here, but in short, cracks “are linear openings that form in materials to relieve stress” and the relative elasticity of the material upon which stress is applied affects the way the pattern occurs.)

In any case, my point here is that Shvetsov was careful when he built this wall, and careful when he broke it, but he did not take it home. He says about this and other installations that he leaves them there – “there” being wherever they were made. Sometimes, it is okay to let big things go.

I am finding that is important that artwork made to be brought to Russia be portable. I say that with no knowledge of the process of shipping work or anything here, except by hearsay. (I did try to ship a book to someone I’ve met here, but it would cost more than the book to get it here, and so I may have to try another strategy.) My gallerist in Los Angeles has mentioned the difficulty of ensuring that a work will arrive in Russia, and several artists and arts managers here in St. Petersburg have reiterated that observation.

Clearly, at the General Staff building of the Hermitage, where, in the east wing devoted to contemporary art, a thorough retrospective of the sculpture of Tony Cragg has been mounted, that is not an issue. State-sponsored shipments may be easier than private ones to rely on.

Clearly, at the General Staff building of the Hermitage, where, in the east wing devoted to contemporary art, a thorough retrospective of the sculpture of Tony Cragg has been mounted, that is not an issue. State-sponsored shipments may be easier than private ones to rely on.

In speaking with Tanja Thorjussen, of the Oslo-based collective Locus, again, I hear about the ways in which practical concerns of portability affect practice. I met her at Locus’ opening at Luda Gallery a few hours after my studio visit with Shvetsov.

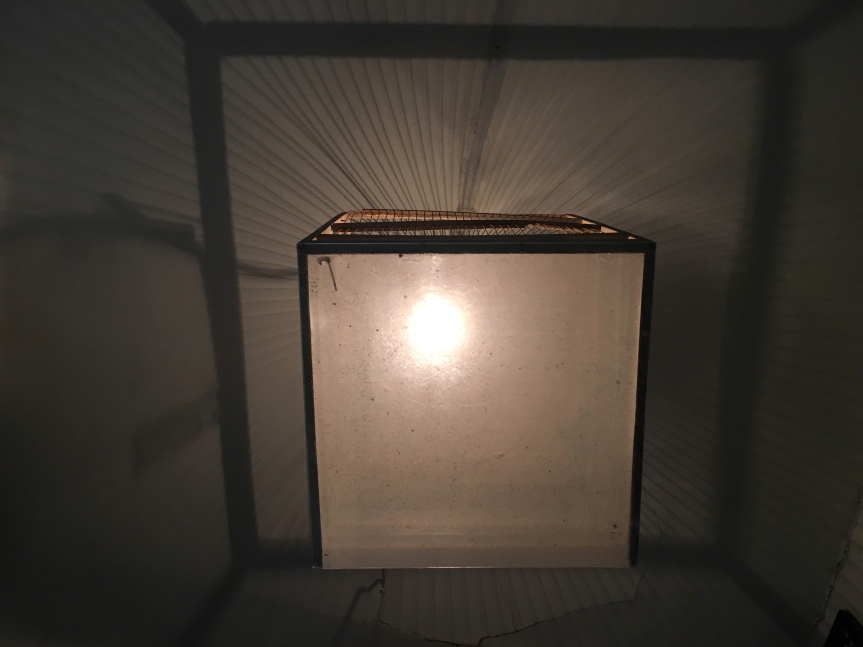

Her contribution to the exhibition, “Collected Stories”, is called “Tupilaq Totem” and is 210 cm x 70 cm. She says that she planned for the piece to be 70 cm wide because it would fit in a tube, and she could carry that tube on the plane with her for her installation in St. Petersburg. She laughingly describes defending the tube against airport authorities who insisted that it was rather big; “It is very fragile,” she maintained over and over again, and won, stowing it in the carry-on of her planes on both legs of her journey.

Her contribution to the exhibition, “Collected Stories”, is called “Tupilaq Totem” and is 210 cm x 70 cm. She says that she planned for the piece to be 70 cm wide because it would fit in a tube, and she could carry that tube on the plane with her for her installation in St. Petersburg. She laughingly describes defending the tube against airport authorities who insisted that it was rather big; “It is very fragile,” she maintained over and over again, and won, stowing it in the carry-on of her planes on both legs of her journey.

The shape of the paper support for the drawing – its narrow linearity – is also of course appropriate for the notion of totem, and totem I did see before hearing that that was the work’s title. The drawing has the essence of an exquisite corpse – that subconscious practice of conjoining unrelated forms – and something also of the essence of the tattoo – that compound pictograph in which a mermaid’s tale is linked to the skull of a harpy or an hourglass becomes a weeping face. All of these associations hint at ritual, and the value of an object associated with magic – something that one might want to clutch closely from place to place.

Thorjussen made this piece based on her observations at a residency in the far north of Norway, near Russia, where she saw the totem’s constituent animals over the course of time. Can still images be time-based? Can they imply time? The quick sketch of a painting, yes. The movement of a camera’s lens. In this case, the sequence of forms ascending or descending the totem does that trick. The picture of course is also not only possible for Thorjussen to have easily gotten into the country for her installation, but also to have easily made on another residency away from home.

This is also true of the other artists’ work in Locus: it can all travel. Marianne Darlén Solhaugstrand showed a grid of lyrical figurative paintings each no bigger than a novel. Thale Fastvold showed small black and white photographs of landscapes the picture plane of which was obstructed by black shapes – also, of course calling attention to that picture plane. Javier Barrios’ pieces were painted, cut, and layered, and also portable – and flat. Amelia Beavis-Harrison made performance out of of course her body and that of her partner in performance, but also out of a fabric she purchased in Mumbai on an artist residency. And so in general, the artwork took license to fly from, in part, its size.

None of this is to make virtue out of smallness, per se, but rather to notice the prevalence of choices as surround portability. It can be large if it changes shape, i.e. rolls or breaks down; it can be small and flat; it can be small and shaped, if supported; it can be a large if the space of the room it ends up in is included in the dimensions with which it is understood; it can be large if left. It is best if the notion of the portable is built into its existence: why it is portable is as important if not more so than the fact that it is.

Likewise, even if not portable, the most important aspect of size is that it be considered not just out of the notion of practical necessity but out of the notion of its marriage to a work. There is no political argument for largeness or smallness that cannot be refuted by its opposite: the Impressionists worked small in order to combat their status quo, but this enabled the bourgeoisie to buy it. Working small makes one’s work generally more accessible to buyers, as dealers tend to price by the square inch on the one hand and on the other because it doesn’t take up a lot of the buyer’s real estate, and so on both hands takes less commitment. It’s also easier to gift or steal. Large work can be written off as self-important, but it can also be read as resistant to commerce, architecturally or spatially responsive, or simply defined by bodily relation and psychoanalytic effect. So the political ramifications of a piece again can’t be pinned specifically to the issue of the work’s size or portability, nor can its goodness. I mentioned at the beginning of this writing some memories of notes on scale from high school and college. Here I remember one from grad school: Charles Ray told me that I would always know a piece was finished when I figured out its scale. Size matters when it matters; it matters when it takes effect.